Building Evidence Basis for Bariatric Surgery

By: Dr. Sherman C. Smith, MD, FACS

Learn more about weight loss surgery at Rocky Mountain Associated Physicians www.RMAP.com (801) 268-3800

It’s been a pleasure to review the latest publications relative to bariatric surgery, establishing a foundation of science from which we can apply major benefit to patients suffering from severe clinical obesity. First, it would be appropriate to first review the currently recognized and effective surgical treatments.

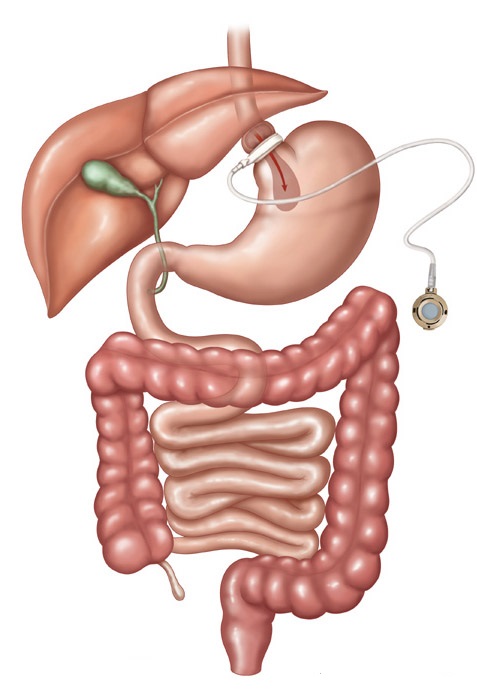

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band (LAP-BAND, Realize Band)

The laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAP-BAND, Realize Band) involves the use of a restrictive device placed just caudal to the esophagogastric junction. The restrictive effect is adjustable by filling an access port by needle on the anterior rectus sheath. It requires adjustments over time to achieve the maximum weight loss benefit. The weight loss at five years ranges from 35-60% loss of excess body weight (EBW), the outcomes largely dependent upon patient compliance with follow up. It is the safest of all surgical procedures in this group, and the 30 day mortality is 0.05%. It is less expensive, reversible and usually only involves an outpatient surgical experience.

Of course there are some disadvantages. The weight loss is slower and patients lose less weight overall on average than with the other procedures. Long term follow up in Europe has been disappointing, and about 40% of the patients have had to have the device either removed, surgically adjusted, or the patients have had unacceptably low amounts of weight lost. Preliminary studies in the U.S. are more promising, but long term studies are still pending.

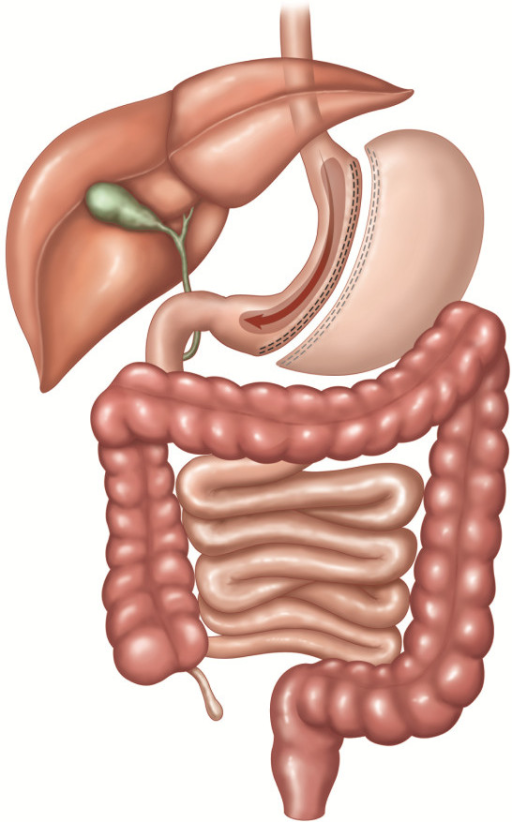

Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

The laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy involves removing 80% of the stomach leaving a thin “sleeve” along the lesser curve. Some of the antrum is usually preserved. There is no foreign body involved and the small bowel is not altered in this operation. Patients tend to lose about 60% of EBW within a year, and seem to maintain that profile through the first five years post-operative years. There is a risk of leak from the staple line in 1-3% of the cases, and stricture at the incisura will occur 1-2% of the time. These are difficult problems to correct and sometimes result in conversion to gastric bypass. Early post-operative heartburn can also be problematic. Mortality at 30 days is 0.2%. This procedure may be performed as the first stage of a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, with plans to return to perform the malabsorptive bowel stage after considerable weight loss in the more massively obese patients. For patients who have had previous bowel surgery for obstruction, or a colostomy, this approach offers the advantage of not having to deal with the adhesions involving the bowel. Patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, and immunocompromised patients may prefer to pursue a sleeve gastrectomy.

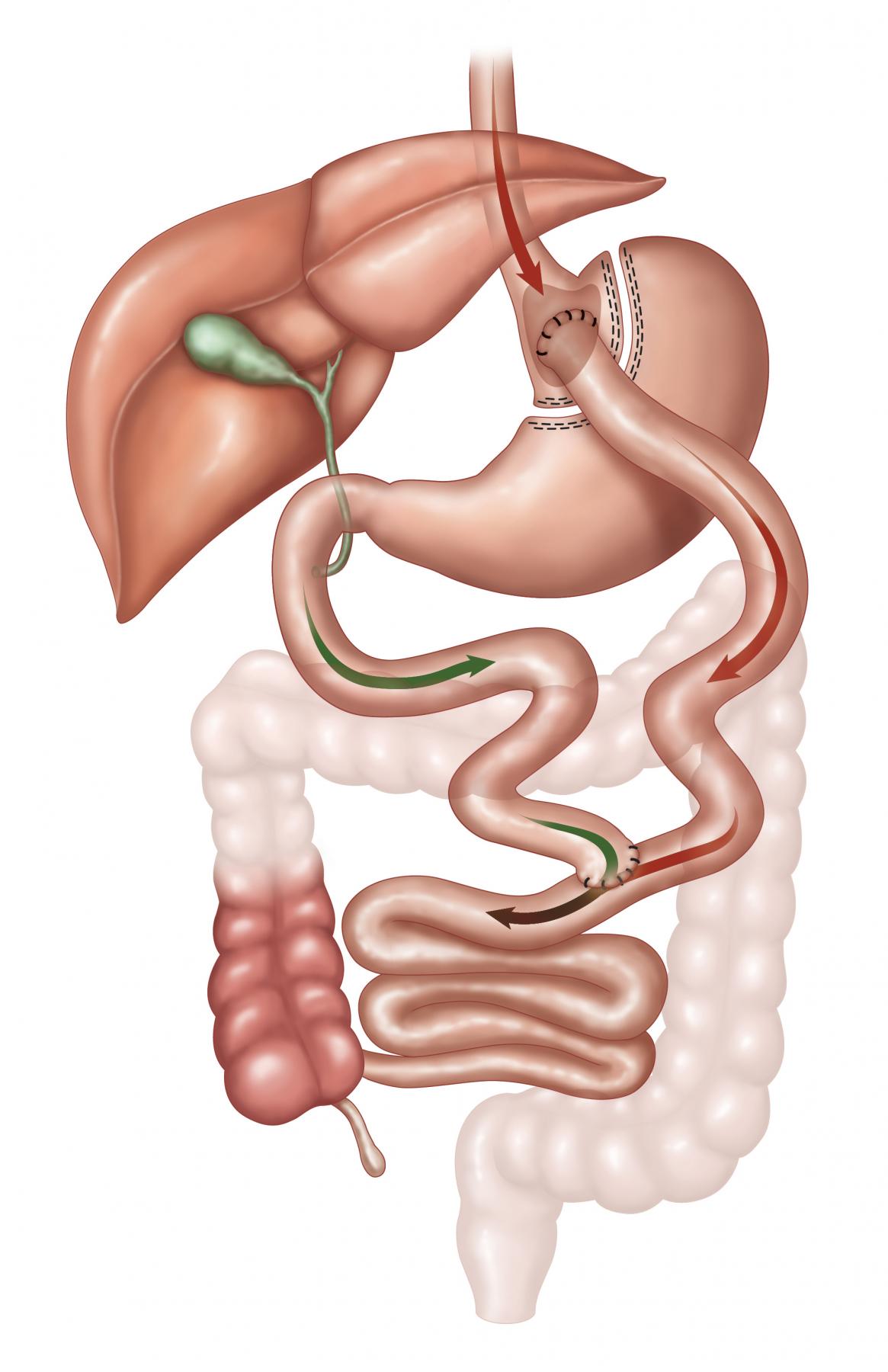

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB)

The laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) has restrictive, metabolic and malabsorptive effects. The best long term data is available with this procedure since it was first done as an open procedure in 1965 with a sling loop, and was converted to a Roux-en-Y in 1973 with markedly improved results with respect to bile reflux gastritis. It remains the most frequently performed procedure in the U.S., and is now most often performed laparoscopically. EBW loss of 60-80% is seen at five years. The 30-day mortality is 0.2%. Diabetics see improvement in their disease within days of the operation, long before significant weight loss has occurred, consistent with a significant metabolic effect through a change in the incretins released from the bowel. This operation is difficult to reverse and may have malabsorption issues particularly with iron, B12 and calcium. Protein malnutrition is extremely uncommon. The dumping syndrome can occur. Anastonotic leaks develop <1% lifetime risk of bowel obstruction is 5%, and anastomotic strictures requiring endoscopic dilation are seen in 5% of patients.

Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch

The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch involves a sleeve gastrectomy, a duodenoenterostomy with preservation of the pylorus, and a short segment common channel in which nutrients are absorbed. This operation is highly malabsorptive, has restriction and is very powerful metabolically. It is suited for those who have a BMI >50, and/or high triglyceride levels. These patients lose 70-90% EBW and diabetes resolution is seen in over 90%, again, as early as 1-2 weeks. Although the true dumping syndrome is not seen, steatorrhea and foul-smelling flatus can be problematic. There are considerable nutritional and vitamin deficiency risks, but most conscientious patients can safely avoid them. Anastomic leaks are seen in 1%, bowel obstruction in 5%, and protein malnutrition in as many as 25%.

A review of some recent publication will be helpful in making an assessment as the value of these aggressive approaches to obesity and its comorbid conditions. The first is “Health Benefits of Gastric Bypass Surgery After 6 Years.”1 This was a prospective study involving three groups. Groups I of 418 patients underwent RYGB, Group II of 417 patient sought RYGB but didn’t have it, and Group III of 321 patients were randomly selected from a population based sample of obese patients not seeking surgery. With a 93% follow up in all groups, there was a 27.7% total body weight (TBW) loss in Group I, 0.2% TBW gain in Group II, and 0% TBW gain in Group buy phentermine low price III. Additionally, 94% of Group I patients has at least 20% decrease in TBW at 2 years and 76% of the patients had at least that amount of weight loss at 6 years.

Diabetes remission defined as a normal HgbA1c was seen in 62% in Group I, 8% in group II, and 6% in Group III. (Remission odds ratios 16.5, p<001 vs. Group II and 21.5, p<.001 vs Group III) The diabetes incidence in Group I = 2%, Group II = 17%, and Group III = 15%.

Hypertension remission/incidence was 42%/16% in group I, 18%/31% in Group II, and 9%/33% in Group III.

Triglyceride remission/incidence was 71%/3% in Group I, 33%/25% in Group II, and 34%/28% in Group III.

Low HDL remission/iincidence in Group I was 67%/5%, in Group II 34%/32%, and in Group III 18%/38%.

Mortality in the groups was comparable with 3% in Group I, 3% in Group II and 1 % in Group III. Suicides and poisonings were not statistically significant in group comparison.

Two randomized controlled trials (RCT) were published in the spring of 2012. The first came from the Cleveland Clinic, “Bariatric Surgery versus intensive Medical Therapy in Obese Patients with Diabetes.”2 This study compared RYGB to sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and to medical therapy. All patients had uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM2) with average HgbA1c=9.2%. The primary end point was HgbA1c of <6.0% after 12 months of treatment. There were 50 patients in each group and a 93% follow-up noted. 12% of the medical group, 42% of the RYGB group, and 37% of the SG group reached the endpoint. The difference between the medical group and the two surgical groups were statistically significant, but between each of the surgical groups they were not. There was improved glycemic control in all groups with an average HgA1c of 7.5% in the medical group, 6.5 in the RYGB group, and 6.6% in the SG group. The medical group lost 5.4 kg, the RYGB group lost 26 kg and the SG group lost 25 kg. Use of medication to control blood pressure, lower lipids, and decrease glucose increased in the medical group, but it decreased in the surgical groups. There were no deaths, but four of the surgical groups’ patients required reoperation.

The next study came out of Cornell University and Rome, Italy and is titled “Bariatric Surgery versus Conventional Medical Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes.”3 This was also RCT involving 60 patients with HgbA1c >7.0%. The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) group, the Biliopancreatic Diversion (BPD) group, and the medical group, each had 20 patients. The end points to define DM2 remission were a FBS of <100mg%, and a HgbA1c<6.5% without pharmacologic therapy. The very impressive rates of remission at 2 years were 0% for the medical therapy group, 75% for the RYGB group and 95% for the BPD group. Total body weight loss was 4.74% of the medical group, 33.3% for the RYGB group, and 33.81% for the BPD group.

Changes in blood pressure were not statistically significant. Decreases in LDL from baseline in the medical group were 20%, RYGB group 17%, and BPD group 57%. Increases in HDL from baseline were 6% in the medical group, 30% in the RYGB group, and 13% in the BPD group. Decreases in the triglyceride levels from baseline were 18% in the medical group, 21% in the RYGB group, and 57% in the BPD group.

Accumulation of this kind of evidence, especially the quality of evidence in RCT’s, confirms the significant decrease in weight, control of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, decrease in cardiovascular risk due to lipid factors, and improvement in hypertension control following bariatric surgery, when compared to medical therapy. The offset of surgical risk has to be considered in these analyses as well, but there are several retrospective studies which point to a lower risk of death for the obese patients, if that patient undergoes bariatric surgery.4,5,6,7,8

Sherman C. Smith, M.D., FASMBS is a general surgeon specializing in bariatric surgery at Rocky Mountain Associated Physicians (RMAP), and performs surgery at LDS and St. Mark’s Hospitals in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is a former assistant clinical professor of surgery at the University of Utah and retired Lt. Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves, having served as a surgeon in operation Desert Storm.

Article was presented at Collegium presentation October 5, 2012.

REFERENCES:

- T. Adam, LE Davidson, et al, “Health Benefits of Gastric Bypass Surgery After 6 Years” JAMA, September 19, 2012 – Vol. 308, Nov. 11 pp.1122-1141

- PR Shauer, et al, “Bariatric Surgery versus intensive Medical Therapy in Obese Patients with Diabetes.” NEJM, March 26, 2012

- G Mingrone, S Panunzi, F Rubino, et al, “Bariatric Surgery versus Conventional Medical Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes.” NEJM, March 26, 2012

- Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. “Lifestyle, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk Factors 10 Years After Bariatric Surgery.” NEJM 2004; 351:2683-93

- Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al, “Long-Term Mortality After Gastric Bypass Surgery.” NEJM 2007; 357:753-761

- Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al, “Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Mortality in Swedish Obese Subjects.” NEJM 2007; 357:741-752.

- “The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Perioperative Safety in the LABS.” NEJM 2009;361445-54

- Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. “Weight and Type 2 Diabetes After Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Am J Med 2009; 122(3);248.e5-256.e5

www.RMAP.com

Rocky Mountain Associated Physicians

801-268-3800

1160 East 3900 South, Suite 4100

SLC, UT 84124

Address: 1521 East 3900 South STE 100

Address: 1521 East 3900 South STE 100 Office: +

Office: +  Fax number (801) 268-3997

Fax number (801) 268-3997 Email: info@rmapinc.com

Email: info@rmapinc.com